Supporting designers in the early stages of designing Plus Energy Buildings is strategic to ensure load reduction while still considering the household practices and enhancing the indoor environmental quality. To achieve this target, it is necessary to make use of effective building energy modeling with a clear view of the simulation results, thus allowing effective communication between the design team and the involved disciplines/stakeholders.

The Cultural-e survey is aimed to identify principal decision-making issues and performance indicators that are meaningful to designers and stakeholders. The result will be analyzed by automated data visualization charts and generate reports.

The survey has been concluded with 101 participants, of which 59 replies have been considered valid including only professionals from the fields of architectural design, environmental design and building physics in the residential sector.

The first part of the survey introduces the participants highlighting their field of work, their level of experience and their preferred energy performance targets. As the survey progresses, it investigates the principal aspects they want to evaluate through the building performance simulation and therefore the performance indicators that they might need.

Who participated in the survey?

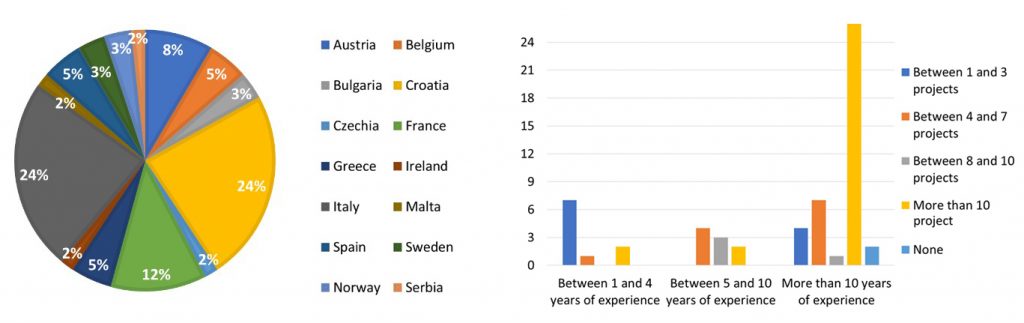

Figure 1 and Figure 2 below show the geographical distribution of the participants and their experience in the field. Most of the participants have a high level of experience and have worked on more than 10 projects in the residential building sector.

| Figure 1 geographical distribution of the participants | Figure 2 the level of experience of the participants |

Based on their experience, the most common energy performance target set in the building design is Nearly Zero Energy Building (25%), followed by Low energy building (19%), Passivhaus (15%), Net Zero Energy Building and Plus Energy Building (6%). It is also interesting that at least one participant per country prefers their own National Building Regulation as target to evaluate the performance of the building.

Among the most used energy certifications in the European panorama, 54% of participants prefer national certifications, 28% international ones, while 18% do not use any certification probably because it is not always required by their clients.

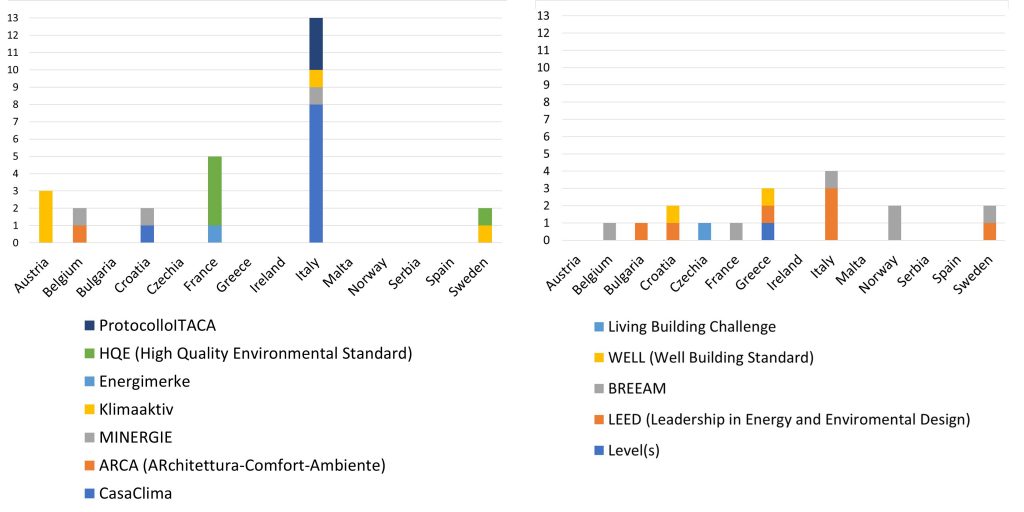

As shown in Figure 4, the most favored national energy certification labels are CasaClima and HQE (High Quality Environmental Standard) chosen respectively by the largest number of the Italian and French designers. Also, probably because these are one of the countries most represented in the survey.

LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) and BREEAM are the most requested international certifications. Only few participants use advanced building energy simulation tools for dynamic simulation of the building’s performance, such as EnergyPlus, Design Builder, TRNSYS, Revit-Green Building Studio and Open Studio.

| Figure 3 National and International energy certification labels |

Which aspects of building performance evaluation does the designer need to investigate? Which methods do they apply and for what purpose?

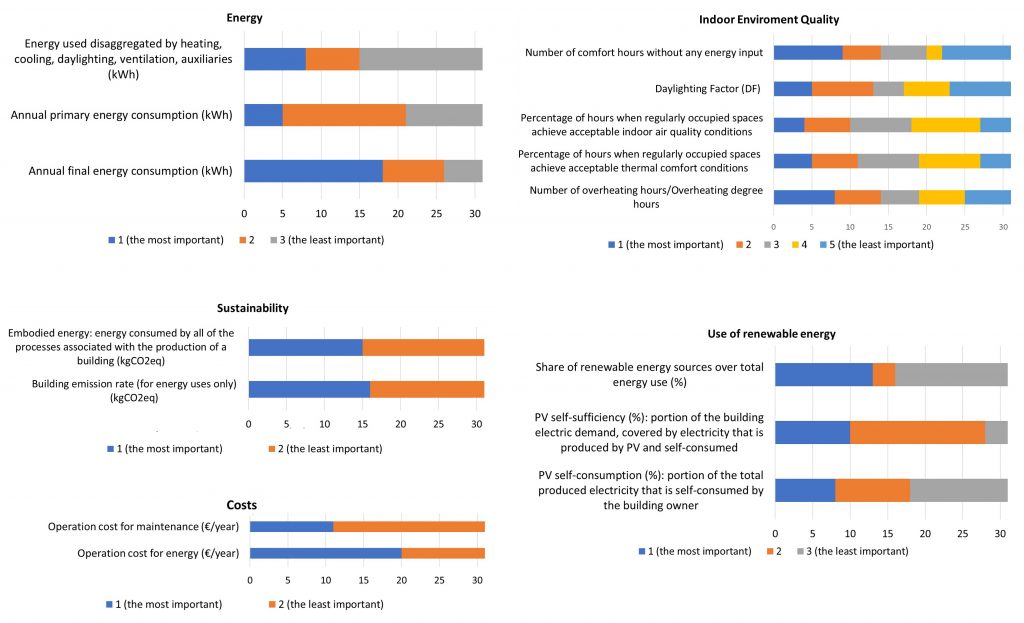

Here are some of the most interesting results! Evaluating the building performance in the early stages of design is an important requirement for designers, so what are the indicators they would need to assess? (Figure 4)

We asked to rate a list of proposed key performance indicators from the least important to the most important according to their daily practice. Unfortunately, only 25 participants responded, which might be due to the innovative nature of the topic of positive energy buildings.

Considering energy indicators, annual final energy consumption is the most preferred energy indicator probably because it portrays an overall picture of the total consumption by the end users.

Among the indicators of indoor environment quality, indoor temperature related aspects (the number of overheating hours and the number of comfort hours without any energy input) are considered the most important while daylighting and indoor air quality are considered less interesting.

The embodied energy and the building emission rate are the principal indicators of sustainability, while to evaluate the costs of the project, designers mainly focus on the operation cost for energy instead of maintenance cost. This aspect could be linked to the size of the residential buildings, as maintenance costs are less vital in one- or two-family houses, compared to multi-family houses of ten or more apartments.

In the field of renewable energy, designers care more about the percentage share of renewable energy sources over total energy use, rather than the ability of the building to match its own load by on-site generation and to work beneficially with respect to the needs of the local grids.

| Figure 4 Performance indicators meaningful for new residential building performance evaluations |

How to make indicators comparable across Europe?

In order to compare the performance of several buildings, also in different climatic contexts, the indicators are usually normalized by transforming them into a more meaningful metric.

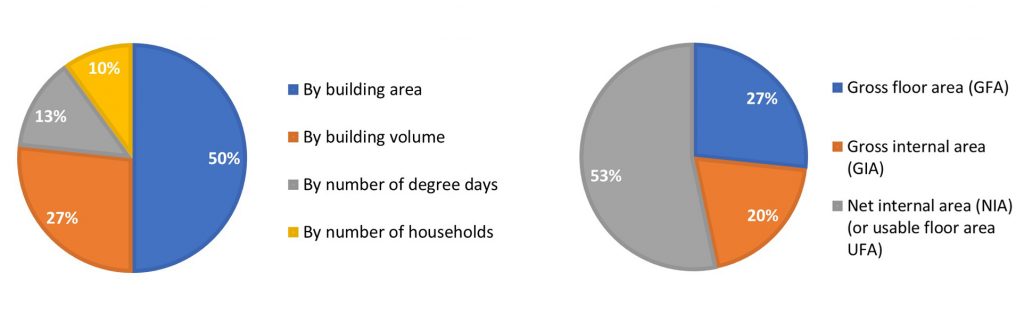

Figure 5 and Figure 6 show that designers prefer to normalize the indicators by building area and in particular by the net one in order to have a balanced comparison.

| Figure 5 Data normalisation of performance indicators | Figure 6 Areas most meaningful for data visualisation by bulding area |

Which problems are designers trying to solve through building energy simulation?

With shorter time intervals and giving greater value to the thermal mass of the opaque building envelope and to the shading systems control, it is possible to design a building with more precision of the energy aspects. For this purpose, the use of dynamic energy simulation tools is generally recommended in building design.

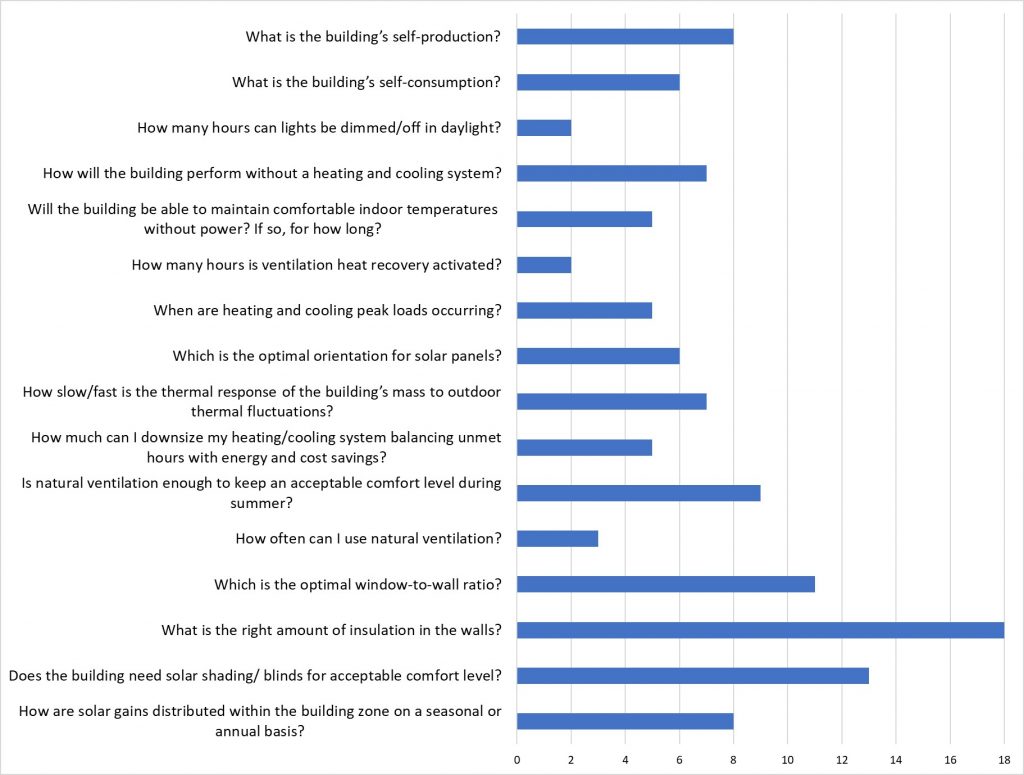

Figure 7 shows the main questions that designers try to answer using these tools and which aspects they need to evaluate. It can be deduced that the dynamic software is not exploited to their maximum potential, as some aspects for evaluating buildings’ performance in detailed are considered less important.

As shown in Figure 7, only a few participants are interested in the correct use of natural ventilation for a good indoor air quality or prefer to exploit the potential of daylight to ensure comfort levels.

In fact, most of them focus their attention on problems that can be evaluated with simple static calculations, such as the amount of insulation of the wall or the optimal window-to-wall-ratio.

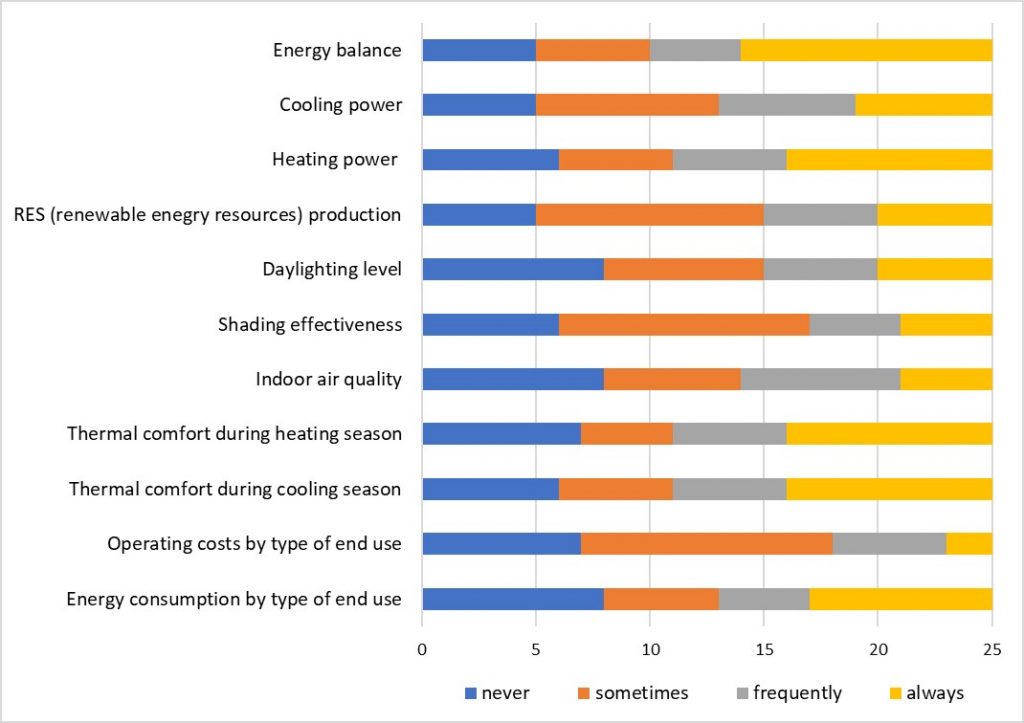

Figure 8 shows in a similar way the frequency in which some aspects of the building performance can be evaluated. Also, in this case more attention is paid to the energy aspects of the building, giving less importance to the indoor air quality and comfort in terms of daylighting level.

| Figure 7 Type of problems solved through building performance simulations |

| Figure 8 evaluation of these aspects using energy simulation tools |

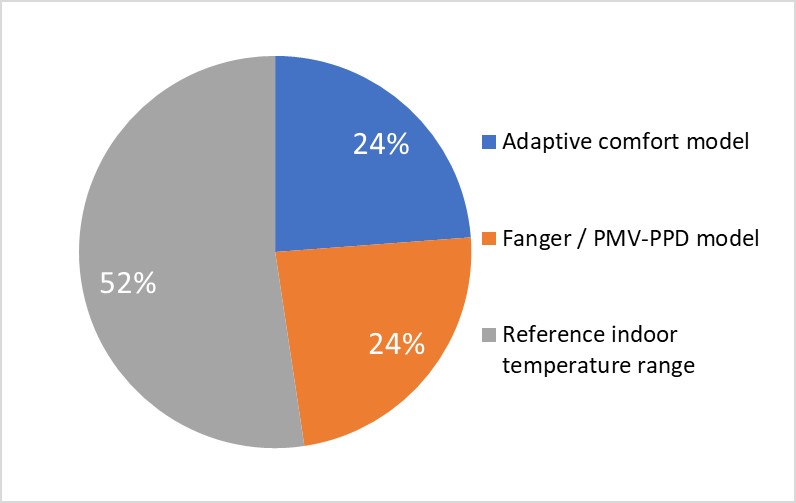

Focusing on the thermal comfort, as Figure 9 depicts, participants prefer to use the reference indoor temperature range to assess the well-being of the building occupants.

The adaptive model, which considers the ability of the occupants to adapt to the prevailing climate, and the Fanger model, which focus of some subjective and environmental variables, are known to a lesser extent.

| Figure 9 Thermal comfort models |

The buildings performance is sometimes evaluated without exploiting the maximum potential of dynamic energy simulation software as it allows a more detailed assessment, not only in terms of energy but also indoor air quality and comfort.

Considering the halved number of participants who concluded the survey, it is clear that the topic of Plus energy building is still not very widespread among designers, probably as a domain that is highly innovative and therefore in the growing phase.

In order to have more awareness of this topic, it could be interesting to organise webinars, workshops or guidelines for designers to highlight the related benefits, which will be done in the context of the Cultural-e project.